Transmutations by Sam Beard (Dispatch Review)

Friday 23 June 2023.

Original post.

(Re)Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats is Desmond Mah’s curatorial debut. Standing beside me in the gallery of the Moores Building, Mah, a Chinese-Australian artist based in Boorloo, tells me that his curatorship arose out of necessity—a familiar tale for many. Yet, even with such short-notice, Mah has succeeded in presenting an eclectic and compelling mix of work.

Mah employs the Chinese chengyu (idiom) "草船借箭" (“borrowing arrows with thatched boats”) as a creative prompt for the exhibiting artists Patricia Amorim, Tami Xiang, Shanti Gelmi, and Deborah Worthy-Collins, alongside himself. The Moores Building has always struck me as a demanding space to curate, with its long and uneven limestone walls, high ceilings, and varying light. (Re)Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats is a commendable curatorial effort, as Mah brings together a diverse selection of works—culturally, materially and topically.

Walking around the gallery, I am excited to unravel the links between the works and the chengyu. 草船借箭 comes from the inventive strategy deployed by Chinese chancellor and sage Zhuge Liang (181–234) during a pivotal battle on the Yangtze River. The tale is most famously recounted by Luo Guanzhong in his Romance of the Three Kingdoms. With fewer arrows than his opponent, Zhuge Liang filled boats with straw mannequins which, on the foggy waters of the river, appeared to be manned vessels. Zhuge’s hot-tempered opponent attacked at once, firing thousands of arrows, which were collected and violently returned by Zhuge’s archers, resulting in victory. Today, 草船借箭 expresses the idea of transforming one’s adversity into advantage—a practice not unfamiliar to many artists. Throughout the exhibition the idiom assumes a variety of forms, echoed in works to various ends.

The first work near the entrance is a multimedia piece by Patricia Amorim. It consists of three hammocks suspended from the ceiling, embroidered with phrases and a self-portrait, overlaid with a video projection of rippling caustics. It is a combination of personal motifs, explains Amorim:

I incorporate three languages—Portuguese, English, and Chinese—into my artwork, embroidering hammocks with words and phrases specific to each culture that refer to women…

The three main elements—embroidery, projection, and suspended hammocks—feel discordant with one another; perhaps intentionally so.

Tami Xiang’s work, Locks of Hometown, is a series of large banners suspended in the centre of the gallery. Mah provides ample space for these large-scale photographic works to hang freely without appearing visually cramped. The photocollages are an amalgamation of two distinct series, one with which I am already familiar, the other brand new. The familiar photocollages depict the woman at the centre of the shocking “Xuzhou chained woman incident”, a harrowing human trafficking case that first came to light in 2022. Xiang combines and remixes material found online to create the portraits, operating upon our natural curiosity for the sitter to cohesively synthesise the story and the images.

The remaining banners attempt to convey Xiang’s experience of being cyberbullied, that arose out of displaying the aforementioned work. She describes how “a group of anonymous people with fake names and profiles [cyberbullied] the models in my artwork, my private life, my images, and even my family.” In these most recent photocollages, Xiang uses her own image, and adorns herself in costumes digitally crafted out padlocks, polypropylene travel bags, and other personal motifs. While sympathetic to the personal nature of the subject matter, I could not help but wonder if the work is complicated by it, and if this might be the reason why these particular images appear visually abstruse and discordant to me.

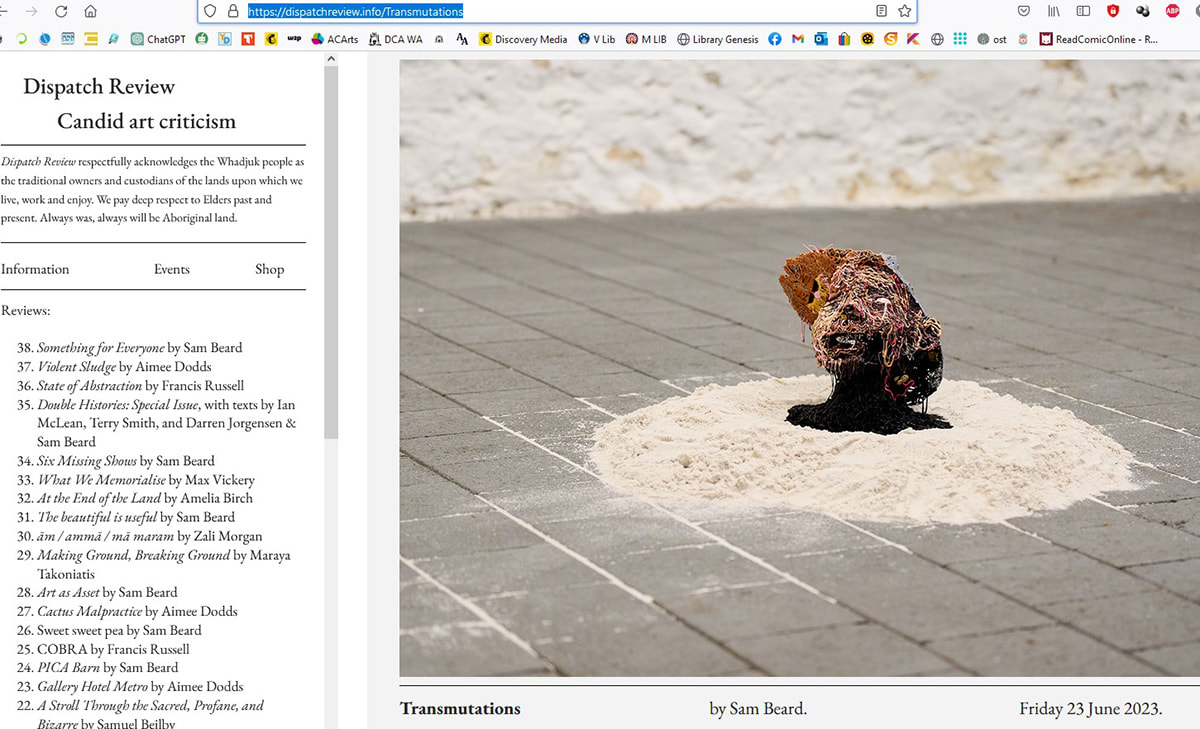

Nearby, Mah creates striking and humorous visuals that are laced with symbols and references which conjure ideas about cultural identity. The first thing I notice is the unusual material qualities of these lively sculptures, crafted with spaghetti-like loops of paint (or paintings with sculptural dimensions, depending on the work). In one sculpture, strands of paint ooze around and around, building upon one another like a coiled pot to form a head, emerging from the floor. Mah explains that the head has broken through what might have been a ceiling for our protruding friendly, but—ah! The head has emerged only to look up and see another ceiling he must break through! A sisyphean task.

The works are playful, and so is Desmond, but there is a serious undercurrent to both the artist and the work. The good will and humour which are undeniable elements engender curiousity and an inclination to explore trickier ideas of cultural hybridity and identity which Mah aims to evoke. Overall, the result is effective.

Shanti Gelmi’s work includes intricate egg drawings and a delicate installation of cracked eggshells with gold painted interiors. The illustrations are flawless. The broken eggshell motif nicely riffs off the idiom. Gelmi appears to borrow from the installation of cracked eggs in her line drawings, embracing the fragility of one media to inform the intricate design of the other. In some ways these seem aesthetically disparate from the neighbouring work, whose presence in the space is perhaps more arresting and less delicate and designerly. At times the tightly designed forms veer too close to illustration. Overall, Gelmi’s works maintain distinctiveness among their neighbours.

Circling around to Deborah Worthy-Collins work, one discovers a fabric, figure-like construction suspended beside nine irregularly shaped frames in a salon-style hang. Within the frames are an assortment of abstract experiments in natural dyes and pigments. Here, Worthy-Collins demonstrates a refined sensitivity for texture and textiles. The central, larger than life installation is a fabric human form, with an absent body; a sheet to dress up as a ghost. It is as playful as Mah’s “head through the ceiling”, and again this playfulness guides one’s mind toward deeper ideas, in this case towards domesticity and gender roles. The red coloured embroidery on the front is flawless, demonstrating a deft hand and skilful control of the material. Visually, and perhaps conceptually, the work is a riddle composed of contradictions: familiar and otherworldly, corporeal and vague, playful and haunting.

There is a lack of labels in the gallery; the walls are bare save for the work itself, and a QR code for additional information. I see this as a curatorial strength: upon entering the exhibition one must determine for themself the relationships, discordances, and/or harmonies between the works. Walking around between Amorim’s projection, Xiang’s photocollages, Mah’s sculptural paintings, Gelmi’s meticulous line drawings, and Worthy-Collins’ textiles, I notice something: the works are as much an experiment in translation and interpretation as the idiom itself.

There is an excellent little book I recently encountered titled Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei by the writer and translator Eliot Weinberger. In it, Weinberger explores 19 different translations of Lu Zhai (“Deer Grove”), a short four-line poem by Wang Wei (c. 700-761). Each page recounts an individual translation, accompanied by Weinberger’s commentary on the form and characteristics of each. Not only is the book a fascinating history of the translation and reception of Wei’s poem, it also points to the role of interpretation in a successful translation. Each translation is always a kind of interpretation.

The Italian writer and semiotician Umberto Eco explores this very idea in Experiences in Translation, where he considered Russian linguist Roman Jakobson’s three modes of translation: intralingual (rewording), interlingual (translation proper), and intersemiotic (“transmutation”, such as the adaptation of a novel into a film). Eco points out that one constant in each of these modes is interpretation:

If all three types of translation are interpretations, did Jakobson not mean that the three types of translation are three types of interpretation, and that therefore translation is a species of the genus interpretation?

The answer is sort of—but that is a topic for another essay (Eco’s, specifically). His central thesis is that translation necessitates various interpretive acts. This is again demonstrated in Luoyang Chen’s thought-provoking foreword to the exhibition catalogue of (Re)Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats. Luoyang notes that the 成语 (“idiom”) loses many of its connotations in translation, most importantly the notion of playfulness. This is a perfect point of departure for considering the connection between Mah’s use of the chengyu as a curatorial prompt and the work included in the exhibition. The idiom is playfully interpreted by many of the artists, though, as we have seen, the results are not necessarily pleasant, and are occasionally haunting or sombre. The five artists were faced with a kind of intersemiotic task: to take the idiom and apply or reimagine it through a visual work. In this sense, perhaps the chengyu is perfectly suited for this task of creative prompt, since it is intended for interpretation, extrapolation, reapplication, and contemplation.

On the day I first visited, Desmond is in the building. He is an excitable soul: eager to welcome visitors and share insights, opinions, interpretations and knowledge. As I wander through the gallery, I observe these interactions with curiosity. Mah’s humour and playfulness is disarming, and soon both he and his visitors are laughing and talking eagerly about the exhibition. His earnest commitment to greeting and showing each visitor around is almost a performance in itself. Perhaps this achieves Desmond’s ambition to bring about critical cultural conversations within the community more than any single artwork.

At the best of times the chengyu proves a fruitful catalyst. When used playfully, and when the artists have allowed the needs of their chosen media to guide their creative choices, the “translation” from idiom to artwork is most successful. Where there has been an overt adherence to the idiom (or concept), an impulse to “fit” the work into the concept, the work appears to have suffered—in these instances feeling forced or lost in translation.

Yet it is these attempts at “translation”, successful or not, that constitute the exciting nature of the exhibition. As Weinberger notes about the translations of Wang’s poem, not all are equally ‘successful.’ However, when read as a whole, the variety results in a deeper appreciation of Wang’s original and the challenges of translation. So, like I finished Weinberger’s book filled with curiosity to read more of Wang’s poetry, I left the Moores Building curious to see more work by these five artists.

As I walked down Henry toward High Street, after the opening of the exhibition, I peeked at the window display of New Editions bookstore and noticed a friend was working the closing shift. I stopped by to say g’day, and began chatting about Mah’s show, to which the bookseller delighted in mentioning that moments ago he had sold a copy of Luo Guanzhong’s Romance of the Three Kingdoms to someone who had just attended Mah’s exhibition: thanks to these five artists, someone else is now curious about borrowing arrows with straw boats (and, by extension, the history and culture of our regional neighbours). This, to me, suggests that the show, along with much of the work, has indeed been a great success.

(Re)Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats,9 - 24 Jun 2023, Moores Building Contemporary Arts Space.

Photographs of (Re)Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats by Liang Xu.

Friday 23 June 2023.

Original post.

(Re)Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats is Desmond Mah’s curatorial debut. Standing beside me in the gallery of the Moores Building, Mah, a Chinese-Australian artist based in Boorloo, tells me that his curatorship arose out of necessity—a familiar tale for many. Yet, even with such short-notice, Mah has succeeded in presenting an eclectic and compelling mix of work.

Mah employs the Chinese chengyu (idiom) "草船借箭" (“borrowing arrows with thatched boats”) as a creative prompt for the exhibiting artists Patricia Amorim, Tami Xiang, Shanti Gelmi, and Deborah Worthy-Collins, alongside himself. The Moores Building has always struck me as a demanding space to curate, with its long and uneven limestone walls, high ceilings, and varying light. (Re)Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats is a commendable curatorial effort, as Mah brings together a diverse selection of works—culturally, materially and topically.

Walking around the gallery, I am excited to unravel the links between the works and the chengyu. 草船借箭 comes from the inventive strategy deployed by Chinese chancellor and sage Zhuge Liang (181–234) during a pivotal battle on the Yangtze River. The tale is most famously recounted by Luo Guanzhong in his Romance of the Three Kingdoms. With fewer arrows than his opponent, Zhuge Liang filled boats with straw mannequins which, on the foggy waters of the river, appeared to be manned vessels. Zhuge’s hot-tempered opponent attacked at once, firing thousands of arrows, which were collected and violently returned by Zhuge’s archers, resulting in victory. Today, 草船借箭 expresses the idea of transforming one’s adversity into advantage—a practice not unfamiliar to many artists. Throughout the exhibition the idiom assumes a variety of forms, echoed in works to various ends.

The first work near the entrance is a multimedia piece by Patricia Amorim. It consists of three hammocks suspended from the ceiling, embroidered with phrases and a self-portrait, overlaid with a video projection of rippling caustics. It is a combination of personal motifs, explains Amorim:

I incorporate three languages—Portuguese, English, and Chinese—into my artwork, embroidering hammocks with words and phrases specific to each culture that refer to women…

The three main elements—embroidery, projection, and suspended hammocks—feel discordant with one another; perhaps intentionally so.

Tami Xiang’s work, Locks of Hometown, is a series of large banners suspended in the centre of the gallery. Mah provides ample space for these large-scale photographic works to hang freely without appearing visually cramped. The photocollages are an amalgamation of two distinct series, one with which I am already familiar, the other brand new. The familiar photocollages depict the woman at the centre of the shocking “Xuzhou chained woman incident”, a harrowing human trafficking case that first came to light in 2022. Xiang combines and remixes material found online to create the portraits, operating upon our natural curiosity for the sitter to cohesively synthesise the story and the images.

The remaining banners attempt to convey Xiang’s experience of being cyberbullied, that arose out of displaying the aforementioned work. She describes how “a group of anonymous people with fake names and profiles [cyberbullied] the models in my artwork, my private life, my images, and even my family.” In these most recent photocollages, Xiang uses her own image, and adorns herself in costumes digitally crafted out padlocks, polypropylene travel bags, and other personal motifs. While sympathetic to the personal nature of the subject matter, I could not help but wonder if the work is complicated by it, and if this might be the reason why these particular images appear visually abstruse and discordant to me.

Nearby, Mah creates striking and humorous visuals that are laced with symbols and references which conjure ideas about cultural identity. The first thing I notice is the unusual material qualities of these lively sculptures, crafted with spaghetti-like loops of paint (or paintings with sculptural dimensions, depending on the work). In one sculpture, strands of paint ooze around and around, building upon one another like a coiled pot to form a head, emerging from the floor. Mah explains that the head has broken through what might have been a ceiling for our protruding friendly, but—ah! The head has emerged only to look up and see another ceiling he must break through! A sisyphean task.

The works are playful, and so is Desmond, but there is a serious undercurrent to both the artist and the work. The good will and humour which are undeniable elements engender curiousity and an inclination to explore trickier ideas of cultural hybridity and identity which Mah aims to evoke. Overall, the result is effective.

Shanti Gelmi’s work includes intricate egg drawings and a delicate installation of cracked eggshells with gold painted interiors. The illustrations are flawless. The broken eggshell motif nicely riffs off the idiom. Gelmi appears to borrow from the installation of cracked eggs in her line drawings, embracing the fragility of one media to inform the intricate design of the other. In some ways these seem aesthetically disparate from the neighbouring work, whose presence in the space is perhaps more arresting and less delicate and designerly. At times the tightly designed forms veer too close to illustration. Overall, Gelmi’s works maintain distinctiveness among their neighbours.

Circling around to Deborah Worthy-Collins work, one discovers a fabric, figure-like construction suspended beside nine irregularly shaped frames in a salon-style hang. Within the frames are an assortment of abstract experiments in natural dyes and pigments. Here, Worthy-Collins demonstrates a refined sensitivity for texture and textiles. The central, larger than life installation is a fabric human form, with an absent body; a sheet to dress up as a ghost. It is as playful as Mah’s “head through the ceiling”, and again this playfulness guides one’s mind toward deeper ideas, in this case towards domesticity and gender roles. The red coloured embroidery on the front is flawless, demonstrating a deft hand and skilful control of the material. Visually, and perhaps conceptually, the work is a riddle composed of contradictions: familiar and otherworldly, corporeal and vague, playful and haunting.

There is a lack of labels in the gallery; the walls are bare save for the work itself, and a QR code for additional information. I see this as a curatorial strength: upon entering the exhibition one must determine for themself the relationships, discordances, and/or harmonies between the works. Walking around between Amorim’s projection, Xiang’s photocollages, Mah’s sculptural paintings, Gelmi’s meticulous line drawings, and Worthy-Collins’ textiles, I notice something: the works are as much an experiment in translation and interpretation as the idiom itself.

There is an excellent little book I recently encountered titled Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei by the writer and translator Eliot Weinberger. In it, Weinberger explores 19 different translations of Lu Zhai (“Deer Grove”), a short four-line poem by Wang Wei (c. 700-761). Each page recounts an individual translation, accompanied by Weinberger’s commentary on the form and characteristics of each. Not only is the book a fascinating history of the translation and reception of Wei’s poem, it also points to the role of interpretation in a successful translation. Each translation is always a kind of interpretation.

The Italian writer and semiotician Umberto Eco explores this very idea in Experiences in Translation, where he considered Russian linguist Roman Jakobson’s three modes of translation: intralingual (rewording), interlingual (translation proper), and intersemiotic (“transmutation”, such as the adaptation of a novel into a film). Eco points out that one constant in each of these modes is interpretation:

If all three types of translation are interpretations, did Jakobson not mean that the three types of translation are three types of interpretation, and that therefore translation is a species of the genus interpretation?

The answer is sort of—but that is a topic for another essay (Eco’s, specifically). His central thesis is that translation necessitates various interpretive acts. This is again demonstrated in Luoyang Chen’s thought-provoking foreword to the exhibition catalogue of (Re)Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats. Luoyang notes that the 成语 (“idiom”) loses many of its connotations in translation, most importantly the notion of playfulness. This is a perfect point of departure for considering the connection between Mah’s use of the chengyu as a curatorial prompt and the work included in the exhibition. The idiom is playfully interpreted by many of the artists, though, as we have seen, the results are not necessarily pleasant, and are occasionally haunting or sombre. The five artists were faced with a kind of intersemiotic task: to take the idiom and apply or reimagine it through a visual work. In this sense, perhaps the chengyu is perfectly suited for this task of creative prompt, since it is intended for interpretation, extrapolation, reapplication, and contemplation.

On the day I first visited, Desmond is in the building. He is an excitable soul: eager to welcome visitors and share insights, opinions, interpretations and knowledge. As I wander through the gallery, I observe these interactions with curiosity. Mah’s humour and playfulness is disarming, and soon both he and his visitors are laughing and talking eagerly about the exhibition. His earnest commitment to greeting and showing each visitor around is almost a performance in itself. Perhaps this achieves Desmond’s ambition to bring about critical cultural conversations within the community more than any single artwork.

At the best of times the chengyu proves a fruitful catalyst. When used playfully, and when the artists have allowed the needs of their chosen media to guide their creative choices, the “translation” from idiom to artwork is most successful. Where there has been an overt adherence to the idiom (or concept), an impulse to “fit” the work into the concept, the work appears to have suffered—in these instances feeling forced or lost in translation.

Yet it is these attempts at “translation”, successful or not, that constitute the exciting nature of the exhibition. As Weinberger notes about the translations of Wang’s poem, not all are equally ‘successful.’ However, when read as a whole, the variety results in a deeper appreciation of Wang’s original and the challenges of translation. So, like I finished Weinberger’s book filled with curiosity to read more of Wang’s poetry, I left the Moores Building curious to see more work by these five artists.

As I walked down Henry toward High Street, after the opening of the exhibition, I peeked at the window display of New Editions bookstore and noticed a friend was working the closing shift. I stopped by to say g’day, and began chatting about Mah’s show, to which the bookseller delighted in mentioning that moments ago he had sold a copy of Luo Guanzhong’s Romance of the Three Kingdoms to someone who had just attended Mah’s exhibition: thanks to these five artists, someone else is now curious about borrowing arrows with straw boats (and, by extension, the history and culture of our regional neighbours). This, to me, suggests that the show, along with much of the work, has indeed been a great success.

(Re)Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats,9 - 24 Jun 2023, Moores Building Contemporary Arts Space.

Photographs of (Re)Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats by Liang Xu.